Words by Caroline Whiteley.

Photos by Kristina Railaite, Lukas Turcksin, Julien Janssens, Karl Magee, Margo Lavigne.

11-minute read

What makes a great club?

Ask ten people and you’ll get ten different answers. The space, the sound, the lights. A good system. The crowd. And of course, there’s always the music.

For some, it’s about the freedom to appear as you are without judgement, for others, it is the freedom to disappear. For many, it’s the encounters with other kindred spirits: the secret corners, the conversations that stretch long after the last track ends. A place where you feel represented, seen, held. A club that’s not just a room for dancing, but a space for experimenting. The best club spaces are built with care and intention, a place for community, built from the ground up.

What makes a great club?

Ask ten people and you’ll get ten different answers. The space, the sound, the lights. A good system. The crowd. And of course, there’s always the music.

For some, it’s about the freedom to appear as you are without judgement, for others, it is the freedom to disappear. For many, it’s the encounters with other kindred spirits: the secret corners, the conversations that stretch long after the last track ends. A place where you feel represented, seen, held. A club that’s not just a room for dancing, but a space for experimenting. The best club spaces are built with care and intention, a place for community, built from the ground up.

{{slider-1}}

From the vegetable gardens that once grew inside Italy’s Space Electronic in Florence to the dripping ceilings of Manchester’s Haçienda, the most legendary club spaces blurred the boundaries between construction and chaos.

For architect Sophia Holst, a perfect club “creates a temporary autonomous zone.” The term, borrowed from anarchist thinker Hakim Bey, describes a fleeting space of self-governance: a zone where the usual rules are suspended, hierarchies dissolve, and people experiment with new ways of being together.

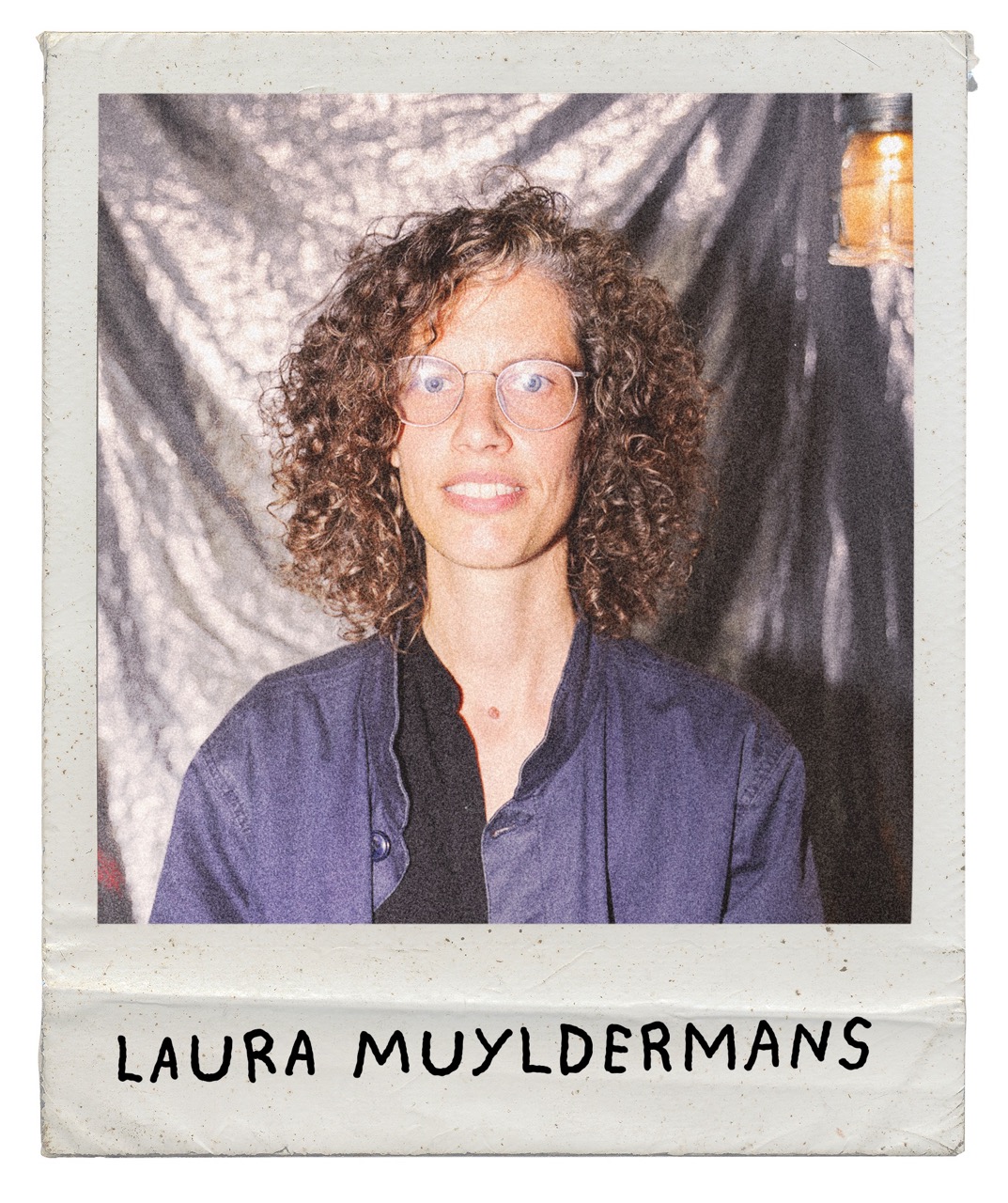

Together with architect Laura Muyldermans and light artist Ofer Smilansky, Holst designed Strato, the club’s main stage for Horst Club, using re-used materials and structural elements from previous seasons.

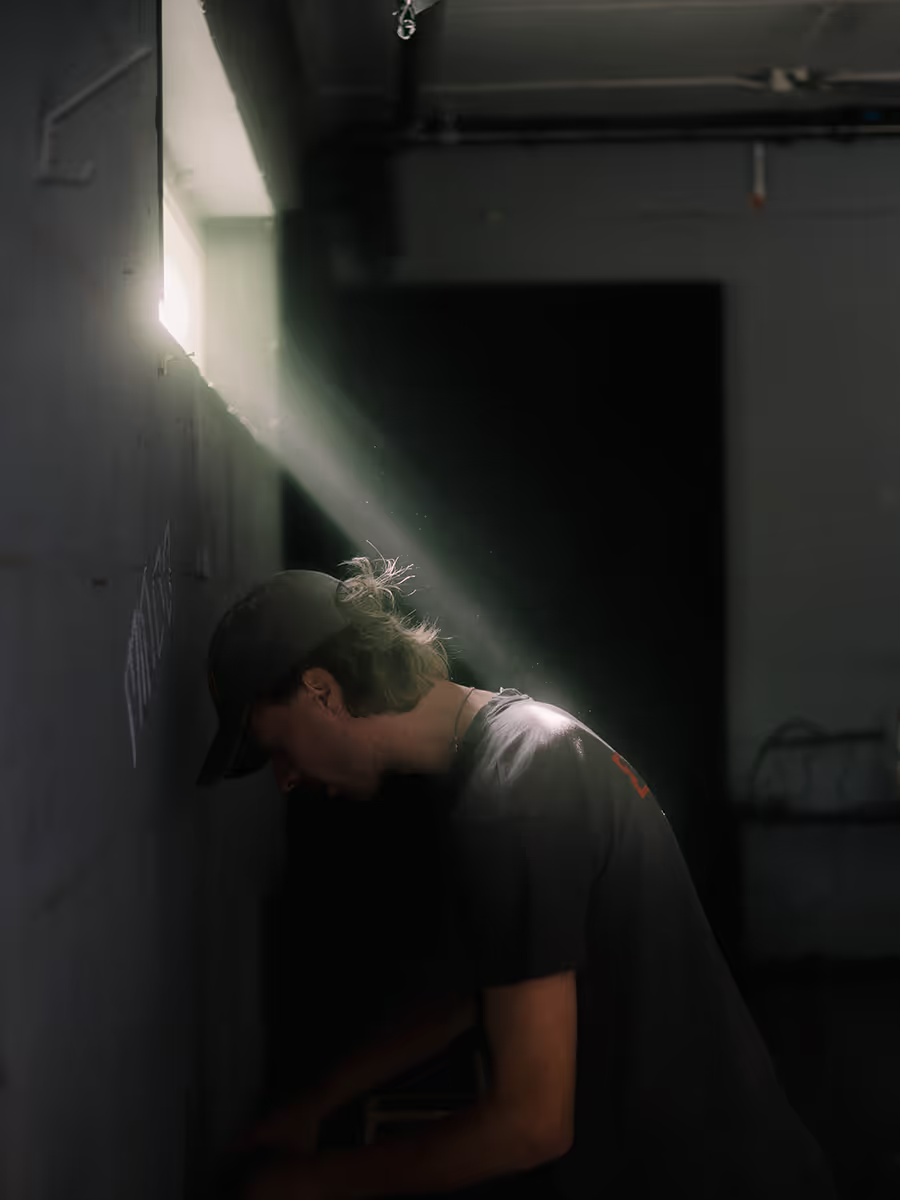

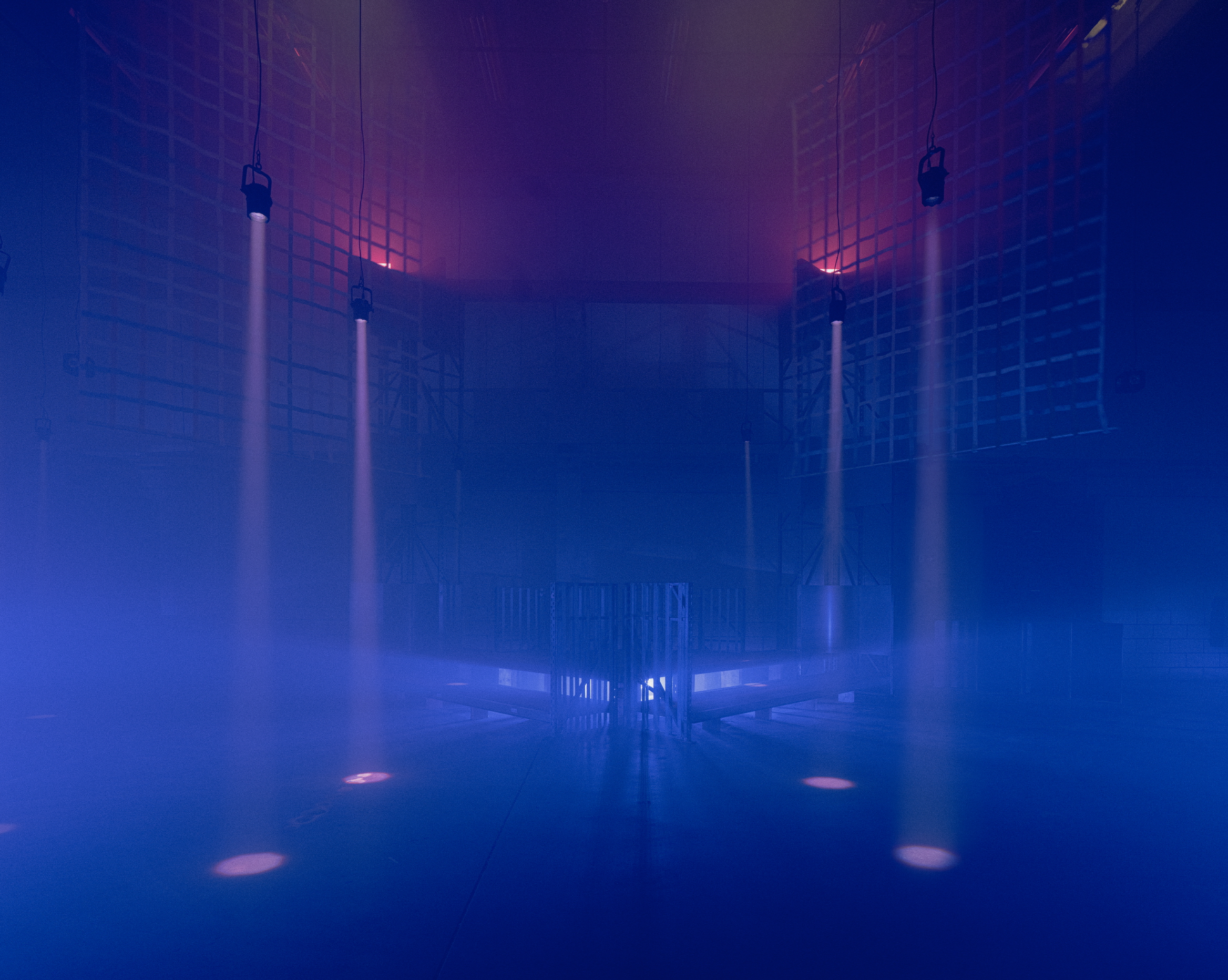

Between ivy-covered hangars at Asiat Park, the sprawling former military base on the edge of Vilvoorde, Horst Club turns the ruins of an old regime into a temporary city of sound, light, and collective movement. “The space itself doesn’t really call for any monolithic or massive central thing,” says Smilansky. “The idea was how to find a language throughout space or some kind of movement that can give the club a feeling of passing of time so it’s not as static as a place.”

For Smilansky, light informs how people move through the space. The lights were built to give dancers shelter, “like a blanket over them, to abstract their contour and give this a wave shape so there’s a coherence between the beginning and the end.”

{{Ofer}}

{{Laura}}

Horst takes that observation and builds upon it. Each structure on site, from the sparse Garage, Rain Room, or the newly built Strato, is iterative. Every season, part of its architecture is dismantled and reassembled by a small army of artists, technicians, volunteers, and scenographers.

“I think one of the first things we decided to do is to come dancing here and to feel what's going on, what works very well, what could be better, what have we learned from it, but how can it also be different?” says Muyldermans. “So it really starts from what it [means] to go to a club and from [the] physical experience.”

The result is a multi-level stage built almost entirely from reused materials — scaffolds, racks, and wooden beams salvaged from previous editions — transformed into a new landscape of diagonals and crosses. “Sometimes you say it’s like six little scenographies or stages within one space,” says Muyldermans.

"Space matters. I love the secret corners, the places where you can decompress, the possibility to step away on your own or to trust that someone will help you step away if you need it." — Erika Evbuomwan

Smilansky’s designs are guided by the metaphor of a slow-moving sun that arcs from night into day, a silent clock marking the club’s twenty-four hour rhythm. “I wanted the club to feel like it breathes,” explains Smilansky. “The space shouldn’t be static. Every shift of colour or brightness should respond to the sound, never just decorate it.”

Suspended across Strato’s ceiling, his lights travel almost imperceptibly from one end to the other, tracing a day’s rhythm in reverse. Nets and translucent surfaces refract the beams into soft gradients. Horst’s resident light designer Liam Van Belle describes the approach as “edgy but theatrical”, outspoken yet minimal. For him, the magic lies in restraint. “It’s not about spectacle,” he says. “It’s about moving atmospheres and telling a story.”

While Strato acts as the architectural grand statement, Garage and the Rain Room are its counterpoints. Conceived by Horst’s in-house community of DJs, light designers and producers Lukas Gallon, Kobe Verhoeve and Max Glaublomme with the Horst Atelier volunteers, the Garage is a no-nonsense room focused on sound clarity. Built by the Dream Plant collective, the light design relies on minimal, hand-built fixtures that frame rather than overwhelm the space.

{{images-1}}

This sensitivity to mood carries across the whole club playground. In the Rain Room, a stage built in 2024 by the Madrid-based studio BURR, the boundaries between indoor and outdoor spaces blur. When the team discovered the skylight leaks that caused rain to fall indoors, they decided not to correct it but to preserve the accident, turning a flaw into the conceptual and sensory anchor of the space: “The Horst team and badweather built this beautiful pond to collect the water. There was something very magical about that,” says BURR’s Jorge Sobejano. “They allowed us to do anything we wanted in the room, but we decided to keep the pond because it was a very special thing.”

By retaining the pond and encouraging vegetation to grow, BURR’s design harkens back to Space Electronic’s 1971 happening where members of the radical architecture design group 9999 Group cultivated a vegetable patch in the middle of the dancefloor. The Rain Room’s skylights and translucent textile canopies create a greenhouse effect, filtering natural light during the day and color projections at night.

{{images-2}}

Inside this glowing, fabric-lined space, perception shifts. “You start to lose references to the outside world, instead feeling like you are in a place that doesn’t belong to your day-to-day,” Sobejano explains. The Rain Room facilitates moments of connection: a space to breathe and slow, tactile form of collective feeling.

“Even before I worked here, what stood out to me about Horst was the focus on community,” says Erika Evbuomwan, Horst’s former Collective Care Coordinator. “Care is the most important expression of community: making sure everyone feels comfortable, trusted and supported among like-minded people. I try to add warmth and a personal touch. I want to care for you, I want you to care for others, and I want us to build this together.”

For her, the evolution of Horst’s club space, from one space to three, has made a real difference. “Space matters. I love the secret corners, the places where you can decompress, the possibility to step away on your own or to trust that someone will help you step away if you need it.” At Horst, there’s a care room, a snooze room, a playroom and other areas to explore. “For a club to design with those options in mind feels considerate. It gives the public as many pathways as possible in the moment.”

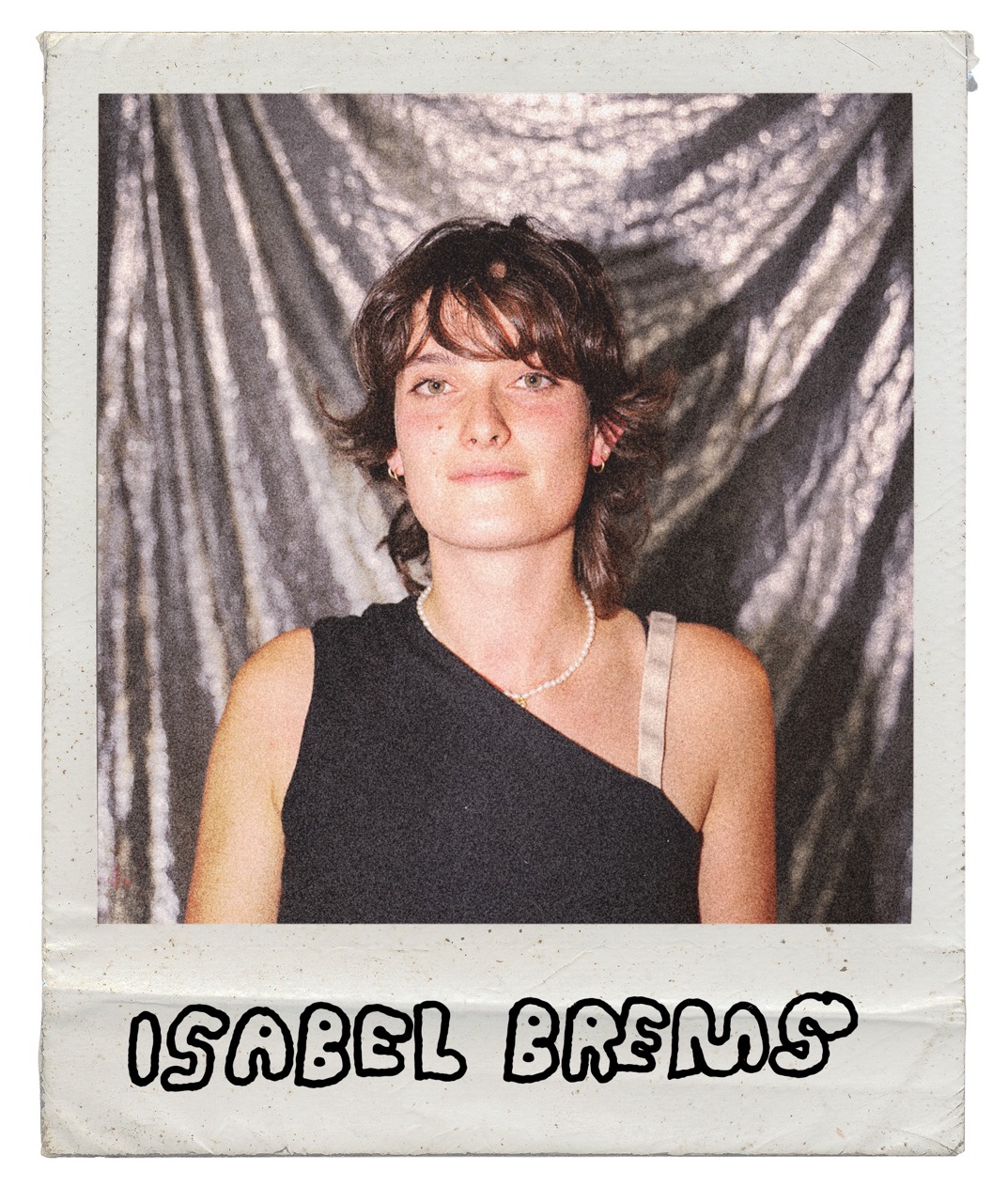

"Party spaces can be overwhelming. I’ve often experienced being at a club and sitting on the cold concrete floor with everyone else." — Isabel Brems

The care team of volunteers and door hosts makes sure that Horst’s physical spaces remain emotionally accessible. “You can put ‘care’ on a billboard, but it is the human, personal contact that makes it real. As long as collective care is present, that human aspect will not fade.”

Textile designer Isabel Brems shares that philosophy. Her off-space installation Root Refuge softens one corner of the club’s industrial terrain into a tactile sanctuary. A tree-like structure draped with eight-metre-long pillows allows for resting, talking, or simply catching breath. “Party spaces can be overwhelming,” she says. “I’ve often experienced being at a club and sitting on the cold concrete floor with everyone else. So I wanted to add something textile, something soft, a place to rest.”

{{slider-2}}

Gestures like the soft corners, the modular pillows and the spaces to pause reveal club architecture as a social practice where each component is designed to listen.

This evolving practice carries the same DIY curiosity and experimental spirit of earlier eras when clubs offered a testing ground for new ways of living together. Imperfection isn’t something to correct; it’s the method itself. “It’s trial and error every time,” light designer Van Belle explains. “We are a big family. After hours, we are very good friends and I think you really notice that in the production and in the scenography.”

Last month, Horst reopened the club at Asiat Park for a new season of twenty-four hour weekends, inviting dancers back into the ecosystem. The same scaffolds shift shape once again, the same lights find new rhythms. The club breathes differently. “With the club, Horst now lives across the seasons,” says Erika Evboumwan. “There is the summer, the winter cosiness, and I appreciate that continuity.”

The architecture, just like the music, holds that rhythm: never static, always reassembled. A reminder that space is not built but lived into being.