Words by Dana Kuehr

Photos by Karl Magee (cover), Willem Mevis & Kristina Railaite

9-minute read

This collective bracing has crystallised into a deliberate practice of care. As of now, Horst has a care team of over 100 staff and volunteers, as well as a care space, a snooze room, a playroom and other ‘chillout’ areas to explore. Erika Evboumwan, Horst’s former collective care coordinator, summarises the Horst care ethos: “I want to care for you, I want you to care for others, and I want us to build this thing together.”

This collective bracing has crystallised into a deliberate practice of care. As of now, Horst has a care team of over 100 staff and volunteers, as well as a care space, a snooze room, a playroom and other ‘chillout’ areas to explore. Erika Evboumwan, Horst’s former collective care coordinator, summarises the Horst care ethos: “I want to care for you, I want you to care for others, and I want us to build this thing together.”

{{slider-1}}

Although contemporary “care teams” feel new, their roots stretch back to the early 1990s, when community-led harm-reduction groups like DanceSafe and Release appeared alongside rave culture. These collectives insisted on what Black feminist thinkers — from Audre Lorde to the Combahee River Collective and bell hooks — had long articulated: that care is political, communal, and essential for survival. Care was never just about safety. It was about establishing the conditions for liberation, joy and rest.

By the time COVID-19 fractured public life, care had already been circulating in nightlife. But the overlapping reckonings of 2020 — Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, surging inequality, a growing awareness of neurodiversity — shifted it from the margins to the centre. Good intentions no longer felt adequate; structure was needed.

Horst recognised this. “After the first post-pandemic year, the festival got a bit wild,” recalls collective care manager Tobha Debacker. “The year after, the organisation decided to have some sort of awareness programme.” What began as a timely intervention has now become a defining feature of the festival and the club.

{{Erika}}

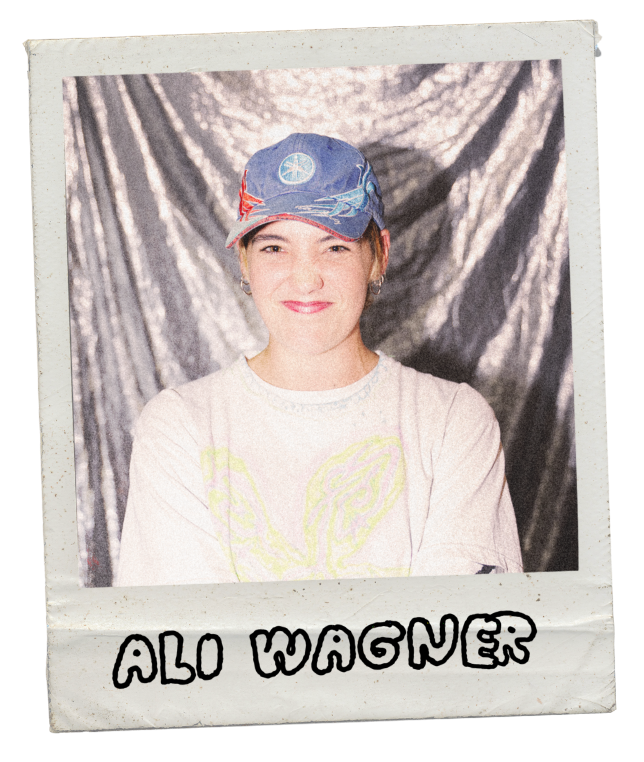

{{Ali}}

Alongside its care programme, Horst tries to infuse care into every aspect of its architecture and atmosphere. Textile artist and scenographer Isabel Brems describes how her sanctuary installation emerged from noticing “how roots grow everywhere, even between concrete,” a metaphor for resilience and grounding. She wanted “a place where people can relax, take a breather, and talk with friends,” adding softness and stillness to an environment that can be overwhelming. “It would be nice if spaces like this could exist anywhere in the world, places to calm down and reflect on what is going on in yourself and around you.”

For Erika Evboumwan, the emphasis is on relationships: “Care is the most important expression of community: making sure everyone feels comfortable, trusted and supported among like-minded people.” Her approach mirrors bell hooks’ insistence that love is a communal practice, not a private sentiment. Erika sees this in how people return, contribute, and slowly strengthen the ecosystem. “Volunteers become regulars,” she notes, “and then take on more responsibility after seeing the process from the inside.”

Ali Wagner, whose project Dancefloor Intimacy centres on accessibility in nightlife, frames it boldly: “Accessibility shouldn’t be an afterthought… imagine if every designer and architect first thought about accessibility.” For Ali, accessibility is not merely logistical but philosophical — a stance aligned with disability justice movements led by queer and POC communities, whose community doctrines deeply shaped contemporary nightlife. The physical space matters, but “the perfect club is when you have the best people inside,” Ali says. “A diverse dance floor where people feel represented.” It is the people, not the spectacle, that produce belonging.

That’s where a more difficult question emerges. When the music stops, people slip back into their own private landscapes of pressure and uncertainty, and the intensity of connection often dissolves. Care can become an annex to the experience rather than a cultural norm lived by everyone in the room.

Erika acknowledges this tension: the care programme “is not the same for every visitor,” which means the work must adapt constantly, listening for the gaps. Trust is key. “You can put ‘care’ on a poster,” she says, “but it is the human, personal contact that makes it real.”

{{images-1}}

Max Rosengren, who greets people at the door, sees the stakes clearly: “Going out — no matter who you are — can be anxiety-inducing… knowing someone has your back can make a huge difference.”

His role is simple but significant: set the tone early, offer grounding guidance, and try to reach everyone, however briefly, who enters the club. But he also notes the limits: “Some people arrive with no intention of engaging in care.” It is a humble reminder that community is not a vibe; it is an intentional practice that must be rehearsed, repeated and renewed. It also recalls the simple fact that community and communication share the same root — to have community, people have to talk to each other.

“Going out — no matter who you are — can be anxiety-inducing… Knowing someone has your back can make a huge difference.” – Max Rosengren

Even as clubs are increasingly recognised as cultural institutions, they remain vulnerable. Rising rents, noise complaints, speculative development and financial stress threaten their existence. A closed venue is not just a cultural loss, but the extinguishing of one of the few spaces where people can inhabit a shared physical world — where they can talk, dream, decompress, engage, and be witnessed by others.

Isabel articulates this well: “I wanted people to go back to their roots… to stop and think about why they are there, whether they are lost, whether it’s time to go home or find a friend.” Her language echoes Audre Lorde’s call for “the transformation of silence into language and action”, calling for spaces where people can pause long enough to recognise themselves and attune with each other.

For Tobha, the political dimension is explicit. Collective care was once “confidential — mostly happening in activist circles, often led by Black communities,” and is now expanding into wider club culture. As care becomes institutionalised, the interesting challenge becomes how to maintain its radical roots.

{{slider-2}}

There may be forms of collective care nightlife has not yet imagined, and Horst knows that care is a journey without endpoint. Horst Club’s monthly rhythm, Erika notes, gives people “enough time to miss it and look forward to the next one.” Self-care through clubbing, then, becomes part of our collective routine — something that grows, takes rest, and resurges again.

As Max says, “It’s not just about having a care team on paper. It’s about being present, showing up, and genuinely making sure the space is safe and comfortable for everyone.” The challenge ahead is to widen the circle so that care is not a specialised side-room but a shared interest. If collective care is to fulfil its promise, it must find ways to persist on the daily — in the complexity of our private struggles, and in the broader fight for spaces where communal life can still take place. Only then can nightlife offer not just escape, but a model for how we can commit to something bigger than ourselves.

.avif)